Mahmoud A. Albreem , Saeed Abdallah , Mohamed Saad , Mahmoud Aldababsa and Khawla Alnajjar

Low Complexity Detectors for Uplink Massive MIMO Based on a Refinement of Linear Algorithms and Efficient Initialization

Abstract: Massive multiple-input multiple-output (mMIMO) plays a crucial role in improving the quality-of-service and achievinghighpowerefficiencyandspectrumefficiencyinbeyond fifth generation communication systems. However, data detection in uplink mMIMO is not a trivial task as the computational complexity increases with the number of antennas. The equalization matrix is diagonally dominant, and hence, most of the existing linear detectors use the diagonal matrix. Unfortunately, detection based on a diagonal matrix may require a high number of iterations to converge, which increases the computational complexity. This is highly challenging because of the large numberofantennason both the transmittingand receivingsides. In this paper, we propose a refinement of six linear mMIMO detectors based on a band matrix formulation to accelerate the convergencerate,andhencereducethecomplexity.Theproposed linear detectors include the Newton iterations method, the Neumann series method, the accelerated over-relaxation method, the successiveover-relaxationmethod,theGauss-Seidel(GS)method, and the Jacobi method. The computation of the band matrix inverse is also presented in this paper and employed in the proposed detectors. In addition, efficient initialization based on thestructureofthebandmatrixisproposed,whichbothimproves the convergence rate and yields a substantial performance gain. Simulations show that the proposed detectors achieve minimum mean-squared error performance with significant complexity reductionevenwhenthenumberofusersapproachesthenumber of base station antennas. It is also shown that the refined detector based on the GS and band matrix achieves the highest performance gain with the lowest computational complexity.

Keywords: 5G, band matrix , data detection , iterative methods , massive MIMO , Neumann series , stair matrix

I. INTRODUCTION

THE relentless growth in the number of wireless devices and the size of data traffic, accompanied by an expanding demand for reliable, low-latency, high data-rate, and energy-efficient connectivity, is driving the development of beyond-fifth-generation (B5G) wireless systems. B5G systems must provide the communication infrastructure to serve highly densely deployed and highly heterogeneous devices that will support a wide range of applications ranging from immersive reality to smart cities and industrial automation [1]. Massive multiple-input multiple-output (mMIMO) technology [2] has emerged as a key solution to improve quality of service (QoS), power efficiency, and spectrum efficiency in B5G wireless systems. In mMIMO, a base station (BS) or access point (AP) equipped with a large number (hundreds or thousands) of antennas serves multiple users using the same time-frequency resources. These systems bring about a huge upgrade in the potential for diversity and multiplexing gains as compared to classical (small-scale) MIMO systems, which can substantially improve both the data rates and the reliability. Moreover, mMIMO systems are less sensitive to noise and highly energy efficient [3], [4].

However, substantial gains in spectrum and energy efficiency are achieved at the cost of increased hardware and computational complexity. In fact, the large number of antennas in the BS translates into a very high signal dimensionality, which in turn can dramatically increase the complexity of essential signal processing tasks in the receiver, such as data detection and channel estimation [5]. Of particular importance is the problem of uplink (UL) detection in mMIMO systems, where the BS needs to decode the transmission of all associated users based on a high-dimensional received signal. In order to achieve the goals of B5G systems, it is critical to achieve this task with high accuracy and minimal latency. Unfortunately, optimal detection techniques such as maximumlikelihood (ML) detection have prohibitively high complexity, making them impractical for mMIMO detection. Hence, the development of appropriate mMIMO detection techniques that provide the best trade-offs between computational complexity and performance has been an active research area in recent years [6], [7]. In [7], authors provide insights on deep learning (DL) based mMIMO UL detectors. Although mMIMO is a mature technology, DL-based detectors are not considered as a mature subject yet. Therefore, researchers’ attention is still concentrating on developing linear detectors for mMIMO systems.

A. Related Work

Significant effort has been expended to develop low complexity detection methods for mMIMO UL systems that can achieve near-optimal performance [5]. Linear detectors, in particular, have attracted renewed interest due to their simplicity and relatively low computational complexity [8]. In classical MIMO systems, the zero-forcing (ZF) and the minimum mean-squared error (MMSE) methods are popular examples of linear detectors that provide a convenient trade-off between performance and complexity. A common requirement of such methods is the inversion of the Gramian matrix [5]. Unfortunately, as the system size scales up from MIMO to mMIMO, this becomes a prohibitively complex operation that would introduce non-trivial latency at the receiver. Moreover, the Gramian matrix is occasionally almost singular, which leads to the system being poorly conditioned [5].

Research efforts have thus focused on developing low complexity alternatives to the high dimensional matrix inversion [8], either through the use of iterative approximate matrix inversion methods, or even by completely avoiding the matrix inversion. Popular methods for approximate matrix inversion consist of Neumann series (NS) [9], [10] and Newton iteration (NI) [11], [12]. Unfortunately, this approach suffers from the existence of matrix multiplications, and hence, high computational complexity. Therefore, it is not considered hardware-friendly. The second approach is to transform the matrix inversion into solving linear equations, starting with an initial estimation. Following a sequence of iterations, the final output shows the solution to linear equations. Examples of such methods include Gauss-Siedel (GS) [13], successive over-relaxation (SOR) [14], conjugate gradient (CG) [15], Jacobi (JA) [16], accelerated over-relaxation (AOR) [17] and Richardson (RI) [18]. In [19], an optimized AOR method is proposed in which the acceleration and relaxation parameters of the AOR method have been carefully selected. In addition, an efficient initialization is proposed to accelerate convergence. In [4], the channel hardening phenomenon is exploited in the initialization stage where the scaled identity matrix and the NI are used. In addition, special matrix structures are utilized instead of the diagonal matrix to achieve faster convergence. In [20], a detection algorithm based on an improved NI method is utilized to reduce the computational complexity. Although these algorithms are obliged to make tradeoffs between complexity and performance, they still require significant iterations’ number to converge, particularly when the receiving antennas’ number is comparable to the transmitting antennas’ number, which is not desirable in the very large-scale integration (VLSI) community [21]. A detailed explanation and extensive comparative study of most of the above-mentioned methods can be found in [8], where the authors provide a numerical analysis of the performancecomplexity profile of each detector.

In both of the above approaches, diagonal matrix has a pivotal role in the method formulation. This is motivated by the fact that the equalization matrix in MMSE is diagonally dominant. It has been observed, however, that in some scenarios, especially when the users’ number draws near the BS antennas’ number, the convergence rate of using the diagonal matrix is slow [22], or the method may not converge [23].

As an alternative to the diagonal matrix formulation, a stair matrix formulation has been proposed in [4], [22]. In the stair matrix, the off-diagonal elements in either the even or the odd row are zeros. The advantages of using stair matrix over diagonal matrix were established in [22], where it was applied in the context of the NS, and the JA, and significant performance enhancement was observed over using the diagonal matrix. The stair matrix’s application was extended to the GS, SOR, RI and NI methods in [6], [23], and significant performance enhancements were also observed. It was also shown that efficient initialization based on a stair matrix results in a significant reduction in complexity.

In addition, a band matrix or banded matrix formulation has been considered as an approximation to the Gramian matrix in the context of mMIMO detection. In the band matrix, elements within a certain number of adjacent diagonals to the main diagonal are non-zero, while the remaining elements are set to zero. The number of non-zero adjacent diagonals are controlled by the bandwidth of the band matrix. The band parameter (λ) influences the precision and the computational complexity. As the λ increases, the complexity increases. In [24], a likelihood ascent search (LAS) detector is proposed, which employs the band matrix in the initialization stage to reduce the proposed detector’s computational complexity. However, authors consider a large band parameter (λ = 20) which results in high computational complexity. In [11], the band matrix is considered with the modified NI method for mMIMO detector. Unfortunately, this scheme may not always converge, and its overall complexity might still be comparable to the exact matrix inversion methods, owing to a large number of matrix multiplications [25].

B. Contribution and Organization

In this paper, we propose a novel approach for the problem of data detection in UL mMIMO systems, motivated by the goal of offering a better balance between computational complexity and performance. Specifically, we propose an efficient data detection scheme that utilizes a band matrix formulation, accompanied by efficient initialization, to achieve near MMSE performance using approximate matrix inversion methods and iterative methods. In matrix theory, a band matrix is a sparse matrix whose non-zero elements are confined to a diagonal band. To our knowledge, the application of the band matrix in mMIMO detection based on iterative methods has not been well investigated. In this paper, we show that the proposed detectors utilizing the band matrix formulation and proposed initialization combine desirable convergence with high-performance gains.

This work’s contributions can be summarized as follows:

· We show that the band matrix is applicable and can be employed in mMIMO detectors due to the desirable convergence rate. Inversion of the band matrix is also presented and utilized in the proposed mMIMO detectors.

· We apply the band matrix in the NS and NI iterationsbased detectors and demonstrate that utilizing the approximate matrix inverse of the band matrix greatly improves the performance and complexity of proposed detectors. In particular, compared to the conventional NI and NSbased detectors where the diagonal matrix is applied, the proposed detectors exhibit a considerable performance gain.

· We propose a refinement of iterative methods (AOR, SOR, GS, and JA) using the band matrix, and demonstrate that the proposed detectors have significantly lower complexity, compared to the cubic complexity of MMSEbased detector, with only minimal performance loss. In addition, compared to the existing iterative methods that utilize the diagonal matrix and stair matrix, the proposed detectors achieved a remarkable performance gain.

· Efficient initialization of the proposed detectors is also proposed to further accelerate the convergence rate and achieve near MMSE performance. The initialization stage employs the band matrix to guarantee a small spectral radius, and hence, fast convergence.

· We use simulations to evaluate the bit error rate (BER) performance, and show that the proposed detectors achieve significant performance improvement over existing detectors where the diagonal and stair matrices were adopted. We also show that the band parameter is crucial to achieving MMSE performance. In addition, we present the performance of proposed detectors as a function of the number of transmitting antennas and band parameter. However, it is noticed that a large band parameter is required when the number of users draws near the number of BS antennas. It is also concluded that band matrixbased detectors can support more users than detectors based on diagonal matrix and stair matrix.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section II provides the system model, including mMIMO structure and preliminary work of the linear MMSE detection, the NS expansion, the NI, AOR, SOR, GS, and JA methods. In Section III, we introduce the band matrix, its properties, and its applicability to mMIMO systems. In addition, we present the proposed mMIMO detectors based on the implementation of band matrix in NS, NI, AOR, SOR, GS, and JA methods. Efficient initialization of the proposed detectors is also proposed in Section III. Section IV presents the complexity profile, in terms of the number of flops, for all the proposed detectors. In Section V, we present and discuss our simulation results. Finally, our conclusions are presented in Section VI.

II. SYSTEM MODEL

In this paper, we consider the UL of a mMIMO system, in which the BS has N antennas and K users of single antenna, i.e., [TeX:] $$N \gg K .$$ The signal received at the BS can be expressed as

Here, [TeX:] $$x=\left[x_1, \cdots, x_K\right]^T \text { and } y=\left[y_1, \cdots, y_N\right]^T$$ are respectively vectors of data signals corresponding to K users and signals received at the BS corrupted by the noise and channel effects. The N × K matrix H denotes the channel matrix and can be represented as [TeX:] $$h=\left[h_1, h_2, \cdots, h_K\right],$$ while the N × 1 vector w denotes the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) vector with mean 0 and covariance [TeX:] $$\sigma^2 I_N .$$ The main role of the mMIMO detector is to estimate x. A plethora of mMIMO detection techniques have been proposed in the literature, ranging from linear detectors to nonlinear detectors and lately machine learning based detectors. This paper focuses on linear mMIMO detectors due to their simplicity and low computational complexity. The development of these detectors has great potential to achieve significant performance gains coupled with a notable reduction in complexity. In what follows, we explore the linear detectors and the relevant low-complexity methods.

A. MMSE Detector

The MMSE data detector can be expressed as

Here, [TeX:] $$W=H^H H+\sigma^2 I_K \text { and } b=H^H y$$ are MMSE equalization matrix and matched-filter output, respectively. Let [TeX:] $$G=H^H H$$ be the Gram matrix or Gramian (which is commonly used in mMIMO linear detectors [26]). Because the different [TeX:] $$h_i$$ are independent, G is diagonally dominant matrix when [TeX:] $$N \rightarrow \infty$$ and K is constant. Therefore, W is also diagonally dominant [26]. In ZF based detectors, the estimated signal can be expressed as

As illustrated in (2) and (3), the linear ZF/MMSE data detection scheme involves the matrix inversion operation, which is computationally expensive, especially in large-scale mMIMO. The inversion of W requires [TeX:] $$O\left(K^3\right) .$$ Therefore, alternative methods are utilized in mMIMO data detection to avoid exact matrix inversion and thus reduce the computational complexity.

B. Neumann Series

A promising solution to the matrix inversion problem is the NS method, which approximates the matrix inversion using matrix multiplications and essentially transforms the matrix inversion of W into the computation of an n-th order matrix polynomial. Since the equalization matrix is diagonally dominant [27], [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$ can be approximated as

where the diagonal matrix D consists of the diagonal entries of W. Equation (4) converges if the condition

is satisfied. A disadvantage of this method is that matrix multiplications are not desired in hardware implementation. Moreover, it requires a large number of iterations to obtain accurate solutions, especially when the ratio between the number of BS antennas and the number of users is relatively small.

C. Newton Iteration

The NI method is derived based on the Taylor series expansion. If [TeX:] $$X^{(0)}$$ refers to the [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$'s initial estimate, then the estimate during the (n+1)th iteration is given by

The initial estimate [TeX:] $$\left(X^{(0)}\right)$$ should be selected properly as it has a significant impact on the number of iterations (n) required for the NI method to converge. Equation (6) exhibits quadratic convergence to [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$ if

where [TeX:] $$X^{(n+1)}$$ matrix represents the approximation of [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$ at iteration n+1. The authors in [28] show that only two iterations of the NI method are sufficient to attain the exact matrix inverse. However, the computational complexities of both the NS and NI based detectors are still high. Nonetheless, the NI method converges faster than the NS method.

D. Data Detection Based on Iterative Methods

In order to maintain reasonable orders of expansion and avoid matrix-matrix multiplications, detectors based on iterative methods (AOR, SOR, GS, and JA) have been proposed. In all these methods, the initial estimate has a great impact on the computational complexity. The initial estimate is commonly set as described in [29]

These iterative methods estimate the received signal without computation of [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$. Alternatively, signal detection based on these iterative methods depends on the diagonal elements (D), the strictly lower triangular entries (L), and the strictly upper triangular entries (U) of the Gramian matrix [30].

The AOR method is a stationary iterative technique, enabling the signal to be estimated as

(9)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)}= & (D-\gamma U)^{-1}[(1-\omega) D+(\omega-\gamma) U+\omega L] \hat{x}^{(n-1)} \\ & +\omega(D-\gamma U)^{-1} b . \end{aligned}$$Here, ω represents the relaxation parameter, and γ denotes the acceleration parameter, both related to the minimum and maximum eigenvalues [31], [32]. It is worth noting that AOR method reduces to JA, GS, and SOR methods for particular values of ω and γ, as detailed below:

In case of γ = ω, the estimated signal [TeX:] $$(\hat{x})$$ based on SOR is presented as

(10)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)}= & (D-\omega L)^{-1}[\omega U+(1-\omega) D] \hat{x}^{(n-1)} \\ & +(D-\omega L)^{-1} \omega b . \end{aligned}$$If ω = γ = 1, the method is called GS, and the signal is estimated as

On the other hand, if γ = 0, ω = 1, we get the JA iterative method, where the signal can be estimated as

which holds if

In mMIMO systems, the condition in (13) can be met with very high probability [33].

On sequential computing platforms, the JA method lacks the robustness and speed of the GS and SOR methods. However, it is suitable for parallel implementation [34].

III. BAND MATRIX AND ITS APPLICABILITY TO MMIMO DETECTION

In this section, we present the band matrix definition and its properties, then show its applicability to mMIMO detection with iterative methods.

A. Band Matrix and Its Properties

Definition 1: A band matrix is a square matrix with zeros after λ elements above and below the main diagonal elements where λ is less than the size of the matrix, i.e., if the matrix is K ×K, then λ < K. In a band matrix, non-zero elements are restricted to the diagonal band, which includes the main diagonal and the secondary diagonals. The parameter λ is referred to as the matrix bandwidth.

Let [TeX:] $$W=\left(W_{i j}\right)$$ be a K × K matrix and [TeX:] $$T=\left(T_{i j}\right)$$ be a band matrix with λ, such that

(14)

[TeX:] $$T_{i j}= \begin{cases}W_{i j}, & |j-i| \leq \lambda, \\ 0, & \text {elsewhere}.\end{cases}$$The equalization matrix (W) can be decomposed as

where [TeX:] $$-L_\lambda \text { and }-U_\lambda$$ are the strict upper and lower entries of [TeX:] $$W-T_\lambda,$$ respectively. Hence, we have that

According to [35], [TeX:] $$\rho\left(T_\lambda^{-1} L_\lambda\right) \lt 1$$ where [TeX:] $$\rho(.)$$ represents the spectral radius.

In the literature, LU decomposition is usually used to find [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}$$ where the jth column of [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}$$ is obtained by solving

Here, [TeX:] $$e_j, V_j, \text { and } T_j$$ represent identity matrix’s jth column, an intermediate vector, and inverse matrix’s jth column, respectively. As noted in [36], the arithmetic operation count for the LU decomposition method is given by [TeX:] $$(4 \lambda-1) k^2+O(k) .$$ Computational complexity of the band matrix inversion can be reduced by employing the twisted decomposition. For [TeX:] $$j=1,2, \cdots, K,$$

where

and

B. Proposed Band Matrix Based NS and NI Detection Methods

Based on (4), the approximation of [TeX:] $$W^{-1}$$ based on the refined NS iteration can be expressed as

where D is replaced with the band matrix (T). Equation (18) converges if the following condition is satisfied

or equivalently the spectral radius [TeX:] $$(\rho\{B\})$$ of the matrix [TeX:] $$B=\left(I-T_\lambda^{-1} W\right)$$ satisfies

NI method can also be initialized using [TeX:] $$X^{(0)}=T_\lambda^{-1},$$ and the first and second iterations are given by

(21)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} & X^{(1)} \approx T_\lambda^{-1}\left(2 I-W T_\lambda^{-1}\right), \\ & X^{(2)} \approx X^{(1)}\left(2 I-W X^{(1)}\right) . \end{aligned}$$Both (18) and (21) depend on computation of the band matrix inverse. Let [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}=M=\left(m_{i j}\right) .$$ Then the jth column entries of M can be written as:

· for [TeX:] $$i=j, j+1, \cdots, j+\lambda-1$$: [TeX:] $$m_{i j}=\frac{1}{d_j},$$ and [TeX:] $$m_{i j}=-\left(l_{i j} m_{j j}+l_{i, j+1} m_{j+1, j}+\cdots+l_{i, i-1} m_{i-1, j}\right),$$

· for [TeX:] $$i=j+\lambda, \cdots, k-1, k$$: [TeX:] $$m_{i j}=-\left(l_{i, i-\lambda} m_{i-\lambda, j}+\cdots+l_{i, i-2} m_{i-2, j}+l_{i, i-1} m_{i-1, j}\right) .$$

Moreover, [TeX:] $$D=\operatorname{diag}\left\{d_1, d_2, \cdots, d_K\right\}$$ is a diagonal matrix where

When [TeX:] $$j=1, L_1 U_1=U L,$$ the number of required flops is [TeX:] $$2 \lambda(\lambda+1) .$$ When [TeX:] $$j=2, \cdots, K,$$ the number of required flops is [TeX:] $$2 \lambda(\lambda+1) K+t_\lambda$$ where [TeX:] $$t_\lambda$$ is a constant related to λ.

C. Proposed Band Matrix Based Iterative Detection Methods

In this subsection, we aim to utilize the band matrix and its inverse [TeX:] $$\left(T_\lambda^{-1}\right)$$ to estimate the signal x directly, instead of approximating the inverse of the Gramian matrix. Recursion is still needed in all approximate methods, which are convergent for any initial guess. In all methods, strict upper and lower elements of the matrices are defined according to λ.

The detected signal based on the refined JA method is

(22)

[TeX:] $$\hat{x}^{(n)}=T_\lambda^{-1}\left(L_\lambda+U_\lambda\right) \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+T_\lambda^{-1} b=\varphi_{J A} \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+T_\lambda^{-1} b,$$where [TeX:] $$\varphi_{J A}=T_\lambda^{-1}\left(L_\lambda+U_\lambda\right)$$ is the iterative matrix of the refined JA method.

The detected signal based on the refined GS method is

(23)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)} & =\left(T_\lambda-L_\lambda\right)^{-1} U_\lambda \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+\left(T_\lambda-L_\lambda\right)^{-1} b \\ & =\varphi_{G S} \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+\left(T_\lambda-L_\lambda\right)^{-1} b, \end{aligned}$$where [TeX:] $$\varphi_{G S}=\left(T_\lambda-L_\lambda\right)^{-1} U_\lambda$$ is the iterative matrix of the refined GS method.

The detected signal based on refined SOR method is

(24)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)}= & \left(T_\lambda-\omega L_\lambda\right)^{-1}\left[\omega U_\lambda+(1-\omega) T_\lambda\right] \hat{x}^{(n-1)} \\ & +\left(T_\lambda-\omega L_\lambda\right)^{-1} \omega b \\ = & \varphi_{S O R}(\omega) \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+\left(T_\lambda-\omega L_\lambda\right)^{-1} \omega b, \end{aligned}$$where [TeX:] $$\varphi_{S O R}(\omega)=\left(T_\lambda-\omega L_\lambda\right)^{-1}\left[\omega U_\lambda+(1-\omega) T_\lambda\right]$$ is the iterative matrix of the refined SOR method. Moreover, the signal can be estimated using the refined AOR based detector as

(25)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)}= & \left(T_\lambda-\gamma U_\lambda\right)^{-1}\left[(1-\omega) T_\lambda+(\omega-\gamma) U_\lambda+\omega L_\lambda\right] \hat{x}^{(n-1)} \\ & +\omega\left(T_\lambda-\gamma U_\lambda\right)^{-1} b \end{aligned}$$or

(26)

[TeX:] $$\begin{aligned} \hat{x}^{(n)}= & \left(T_\lambda-\gamma L_\lambda\right)^{-1}\left[(1-\omega) T_\lambda+(\omega-\gamma) L_\lambda+\omega U_\lambda\right] \hat{x}^{(n-1)} \\ & +\omega\left(T_\lambda-\gamma L_\lambda\right)^{-1} b \end{aligned}$$and the iteration matrix of the refined AOR is

(27)

[TeX:] $$\varphi_{A O R}(\gamma, \omega)=\left(T_\lambda-\gamma L_\lambda\right)^{-1}\left[(1-\omega) T_\lambda+(\omega-\gamma) L_\lambda+\omega U_\lambda\right] .$$Therefore, (26) can be simply re-written as

(28)

[TeX:] $$\hat{x}^{(n)}=\varphi_{A O R}(\gamma, \omega) \hat{x}^{(n-1)}+\omega\left(T_\lambda-\gamma L_\lambda\right)^{-1} b .$$Appropriate selection of γ and ω is crucial for performance gains. In conventional AOR, they are selected as [TeX:] $$0 \leq \gamma \lt \omega \leq 1 .$$ The refined AOR method converges if [TeX:] $$\rho\left(\varphi_{A O R}(\gamma, \omega)\right) \lt 1$$ and [TeX:] $$\omega \neq 0.$$

D. Convergence Rate

Definition 2: A K×K matrix [TeX:] $$M=\left(m_{i, j}\right)$$ is said to be strictly diagonally dominant (SDD) if

Also let [TeX:] $$Q=\left(Q_{i, j}\right)$$ be a K×K matrix, then the spectral radius is given by

where

(30)

[TeX:] $$\rho_i=\frac{\sum_{j=1}^K\left|Q_{i, j}\right|}{\left|M_{i, i}\right|-\sum_{j=1, j \neq i}^K\left|M_{i, j}\right|} .$$If W is an M−matrix and [TeX:] $$0 \leq \gamma \leq \omega \leq 1$$ with [TeX:] $$\omega \neq 0,$$ then the iterative method is convergent and the spectral radius [TeX:] $$\rho\left(\varphi^{(\lambda)}\right) \lt 1 .$$ Let [TeX:] $$M=T_\lambda$$ and [TeX:] $$Q=L_\lambda+U_\lambda$$ in the refined JA method, [TeX:] $$M=T_\lambda-L_\lambda$$ and [TeX:] $$Q=U_\lambda$$ in the refined GS method, and [TeX:] $$M=T_\lambda-\omega U_\lambda \text { and } Q=U_\lambda$$ in the refined SOR method. Obviously, the matrix M is SDD. Therefore, M and Q satisfy the condition in (29) and

Based on (29) – (31) and by a little computation, one can see that [TeX:] $$\rho^{(1)} \geq \rho^{(2)} \geq \rho^{(3)} \geq \cdots \geq \rho^{(K)}=0 .$$

It should be noted that

We can choose a natural number [TeX:] $$\lambda \leq K$$ such that [TeX:] $$\rho\left(\varphi_{J A}^{(\lambda)}\right), \rho\left(\varphi_{G S}^{(\lambda)}\right), \rho\left(\varphi_{S O R}^{(\lambda)}\right), \text { and } \rho\left(\varphi_{A O R}^{(\lambda)}\right)$$ are sufficiently small. Further details regarding the convergence analysis can be found in [37].

E. Initial Estimation

As shown in (8), the conventional selection of the initial estimate depends on the diagonal matrix. Although iterative methods are convergent for any initial vector, we propose to exploit the band matrix to determine the initial estimate where we can obtain performance gain using a small number of iterations. In this paper, we propose to select the initial estimate for the proposed detectors based on the band matrix as

IV. COMPUTATIONAL COMPLEXITY

It is worth-noting that the for a band matrix with bandwidth [TeX:] $$2 \lambda+1 \text { is } O\left(K \lambda^2\right) .$$ In addition, the complexity of [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}$$ is [TeX:] $$O\left(K \lambda^2\right) .$$ In all proposed methods, it is initially necessary to construct the band matrix that has the complexity of [TeX:] $$O\left(K^2\right)$$ [37]. The computational complexity is divided into two stages: initialization and iteration. During initialization, computing [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}$$ involves [TeX:] $$2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ flops. Table I shows the total number of arithmetic operations required to compute [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}.$$ It is shown that the computation of [TeX:] $$T_\lambda^{-1}$$ based on the implementation of twisted decomposition is about twice as fast as the implementation of LU decomposition in (17). It is also clear that the number of flops increases monotonically as the bandwidth parameter (λ) increases. The second stage (detection stage) includes the nth iteration. The number of required flops in one iteration of the JA based detector is given by (22) is [TeX:] $$K^2+2 \lambda K+K-2 \lambda-1,$$ and hence the total number of flops of the JA based detector is [TeX:] $$n\left(K^2+2 \lambda K+K-2 \lambda-1\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda .$$ For the GS based detector given by (23), the components of [TeX:] $$\hat{x}^{(n)}$$ can be calculated successively, and hence, there is no need to compute [TeX:] $$\left(T_\lambda-L_\lambda\right)^{-1} .$$ Therefor, the number of flops in one iteration is [TeX:] $$\lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right),$$ and hence, the total number of flops is [TeX:] $$n \lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda .$$ For the SOR based detector, the number of flops in one iteration is [TeX:] $$4 \lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right),$$ and hence, the total number of flops is [TeX:] $$4 n \lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda .$$ The AOR based detector approximately requires [TeX:] $$n \lambda\left(7 K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda .$$ The NI based detector attains MMSE performance when n=2. Based on (20), the number of flops required for the first and second iterations of the NI based detector is [TeX:] $$K(4 \lambda+1)-2 \lambda^2-2 \lambda$$ and [TeX:] $$K^2(8 \lambda+2)-K\left(4 \lambda^2+4 \lambda-1\right),$$ respectively. Hence, the total number of flops for the first and second iterations is [TeX:] $$K(4 \lambda+1)-2 \lambda^2-2 \lambda+K^2(8 \lambda+2)-K\left(4 \lambda^2+4 \lambda-1\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda .$$ In all the aforementioned methods, it is also observed that the complexity of the proposed detectors is quadratic.

TABLE I

| Flops | |

|---|---|

| j = 1 | [TeX:] $$2 \lambda(\lambda+1)$$ |

| [TeX:] $$j=2, \cdots, K$$ | [TeX:] $$2 \lambda(\lambda+1) K+t_\lambda$$ |

| Total | [TeX:] $$2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

Table II summarizes the computational complexities of the proposed detectors. It is also clear that the computational complexity depends on the number of iterations (n) and the bandwidth (λ). Moreover, the MMSE computational complexity is reduced from cubic in the number of transmitting antennas [TeX:] $$O\left(K^3\right)$$ to approximately [TeX:] $$O\left(K^2\right)$$. Table III presents a comprehensive comparison of execution times across the proposed detectors under identical hardware/software conditions (10,000 Monte Carlo runs, MATLAB R2021a, 3.2GHz with 64 GB DDR5, Intel i9-14900K). The results illustrate the computational advantages of all proposed detectors.

TABLE II

| Detector | Number of Flops |

|---|---|

| Refined AOR | [TeX:] $$n \lambda\left(7 K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

| Refined SOR | [TeX:] $$4 n \lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

| Refined GS | [TeX:] $$n \lambda\left(K^2+3 K\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

| Refined JA | [TeX:] $$n\left(K^2+2 \lambda K+K-2 \lambda-1\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

| Refined NI | [TeX:] $$K(4 \lambda+1)-2 \lambda^2-2 \lambda+K^2(8 \lambda+2)-K\left(4 \lambda^2+4 \lambda-1\right)+2 \lambda K^2+(3 \lambda+5) \lambda K+t_\lambda$$ |

TABLE III

| Method | Number of iterations (n) | Execution time |

|---|---|---|

| MMSE | - | 0.387 |

| Refined AOR | 1 | 0.085 |

| Refined SOR | 1 | 0.074 |

| Refined GS | 1 | 0.068 |

| Refined JA | 1 | 0.080 |

| Refined NI | 2 | 0.101 |

| Refined NS | 2 | 0.114 |

V. SIMULATION RESULTS

In this section, we present our simulation results for all the proposed detectors. In particular, we showcase the BER versus SNR for each of the proposed detectors and compare it with the performance of conventional detectors. Computational complexity is also demonstrated in terms of the number of flops. Both performance and complexity are presented as functions of the number of transmitting antennas, the number of iterations and the parameter λ. For the number of receiving antennas, we consider both 128 and 256 antennas. The channel matrix H is generated using Rayleigh fading, and is assumed to be perfectly known at the receiver. Our results are averaged over 10,000 instances of the channel matrix H. We consider 64-QAM throughout our simulations.

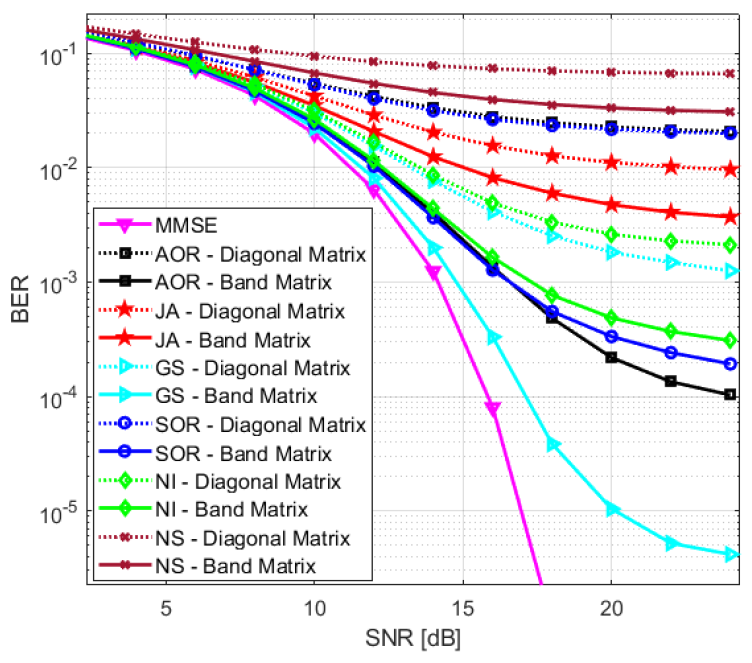

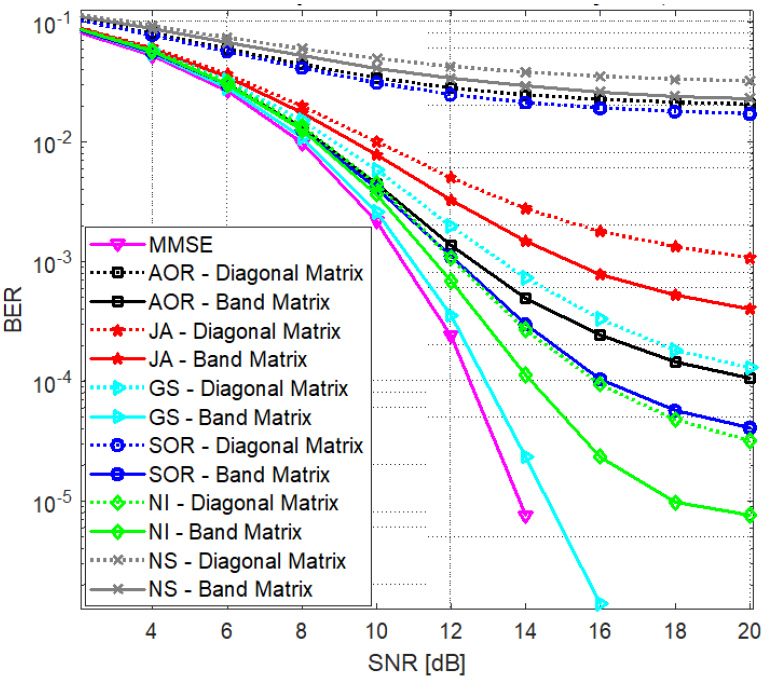

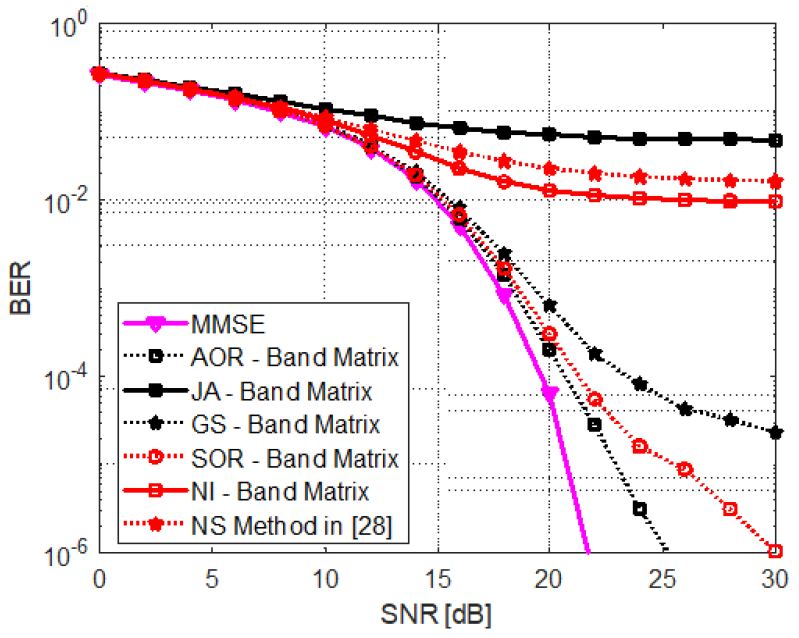

In Fig. 1, we show the BER performance of all the detectors (AOR, JA, GS, SOR, NI, and NS), based on both the diagonal matrix and the band matrix, assuming a 16×128 setup, and only a single iteration n=1 for all the iterative algorithms. The bandwidth λ of the band matrix is set to 1. As a benchmark, we also show the performance of the MMSE detector. For all the proposed algorithms without exception, the band matrix version offers significantly better performance to the diagonal matrix version, especially in the higher SNR range. For instance, the band matrix version of the GS method exhibits a gain of more than 10 dB over the diagonal matrix version at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-3} .$$ For the NI method, the gain is [TeX:] $$\approx 9.5 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=2 \times 10^{-3} .$$ For the JA method, the gain is more than 10 dB at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-2} .$$ For the NS method, a gain of more than 15 dB is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=0.7 \times 10^{-1} .$$ A gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 15 \mathrm{~dB}$$ is also observed for the SOR at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=0.2 \times 10^{-1} .$$ For the AOR, a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 10 \mathrm{~dB}$$ is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=0.2 \times 10^{-1} .$$ Hence, for all the considered methods, and for the same number of iterations, the use of the band matrix results in substantial gains. These gains are achieved at minimal extra cost in terms of computational complexity, which establishes the superiority of the band matrix formulation. It is worth mentioning that the band matrix version of the GS provides performance closest to MMSE, with a gap of less than 1 dB at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-3},$$ although this gap increases at lower BER values.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

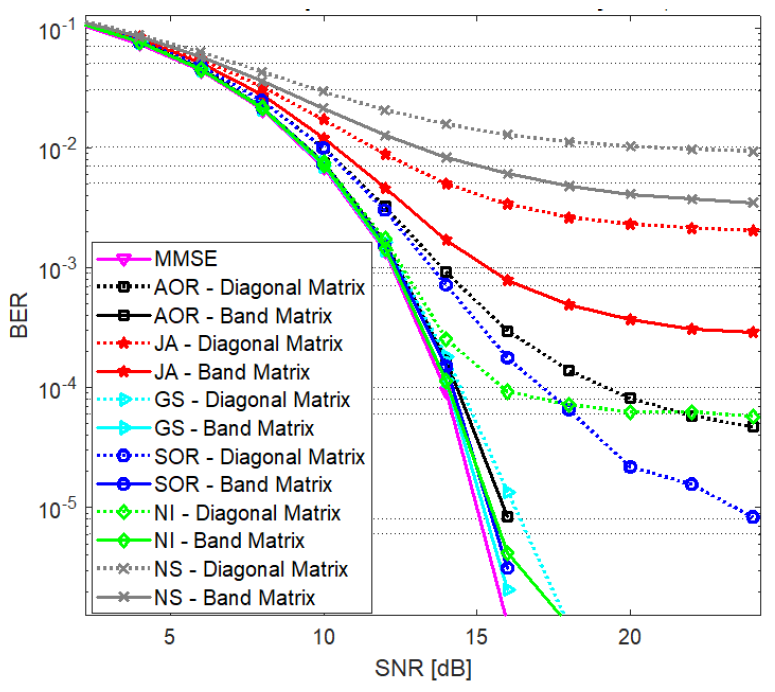

The same simulation is repeated in Fig. 2, but this time using n = 2 iterations for all the proposed methods. It is again observed that the band matrix version of all the methods is superior to the diagonal version. For instance, the band matrix version of the GS offers a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 2 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-5}.$$ For the NI, the performance of the two versions is initially almost overlapping at low SNR, but the gap in favor of the band matrix version increases with SNR, such that there is a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 10 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=0.5 \times 10^{-4}.$$ The SOR method shows a gap of [TeX:] $$\approx 2.7 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-4}.$$, which increases to [TeX:] $$\approx 10 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-5}.$$ For the JA method, the gain is [TeX:] $$\approx 10 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=2 \times 10^{-3}.$$ For the NS, a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 11 \mathrm{~dB}$$ is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-2}.$$ For the AOR, the gain is approximately 2 dB at BER of [TeX:] $$10^{-3},$$ but increases to [TeX:] $$a \approx 9 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=4 \times 10^{-5}.$$ Hence, the band matrix version again provides superior performance to the diagonal matrix for all algorithms, though for some methods the gap is small at low SNR and becomes more substantial at high SNR. It is also observed that the performance of the band matrix version of the GS almost overlaps with the MMSE for this case, while the band matrix version of the NI and the SOR are also very close to the MMSE.

In Fig. 3, we consider the same simulation setup as Fig. 2, but the bandwidth λ of the band matrix is increased to 2. It is observed that all the methods exhibit improved performance as the bandwidth increases to 2. In fact, the performances of the band matrix versions of the GS, NI, SOR, and AOR are almost indistinguishable from the MMSE, while the JA and NS also show significant gains. These gains are achieved at the cost of a moderate increase in computational complexity due to the higher value of λ.

Fig. 3.

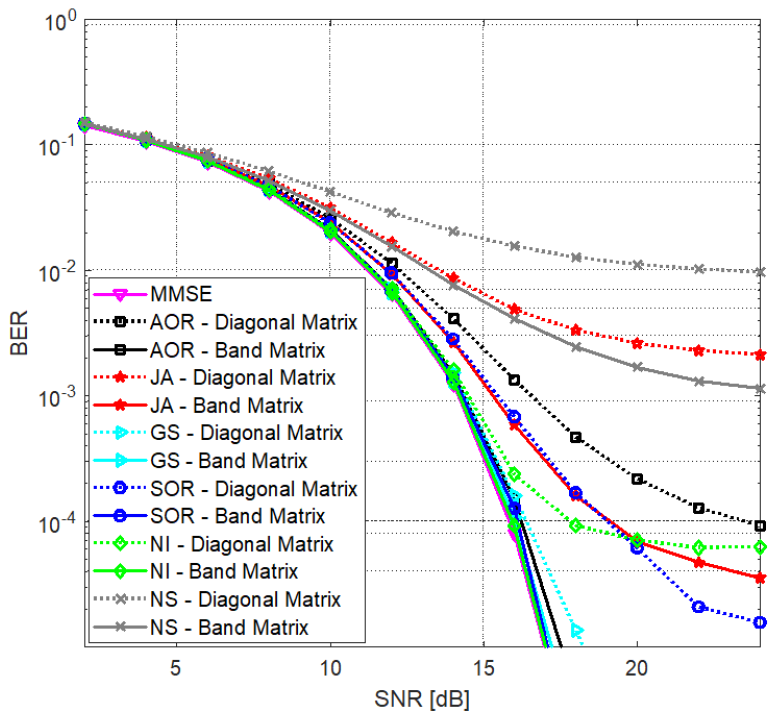

In Fig. 4, we scale up the size of the system by increasing BS antennas’ number to 256 and users’ number to 24, while using a single iteration for all methods (n=1) and a bandwidth of λ = 1 for the band matrix. It is clear that as the system size is almost doubled, the band matrix version is still superior to the diagonal version for all methods. In particular, it is observed that band matrix GS outperforms the diagonal GS by [TeX:] $$\approx 6 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-4}.$$ For the NI, a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 2 \mathrm{~dB}$$ is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-4}.$$ For the JA, a gain of more than 4 dB is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=10^{-3}.$$ For the NS, a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 8 \mathrm{~dB}$$ is observed at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=5 \times 10^{-2}.$$ A huge improvement in the performance of the SOR is also observed. The band matrix GS performs closest to the MMSE, followed by the band matrix NI.

Fig. 4.

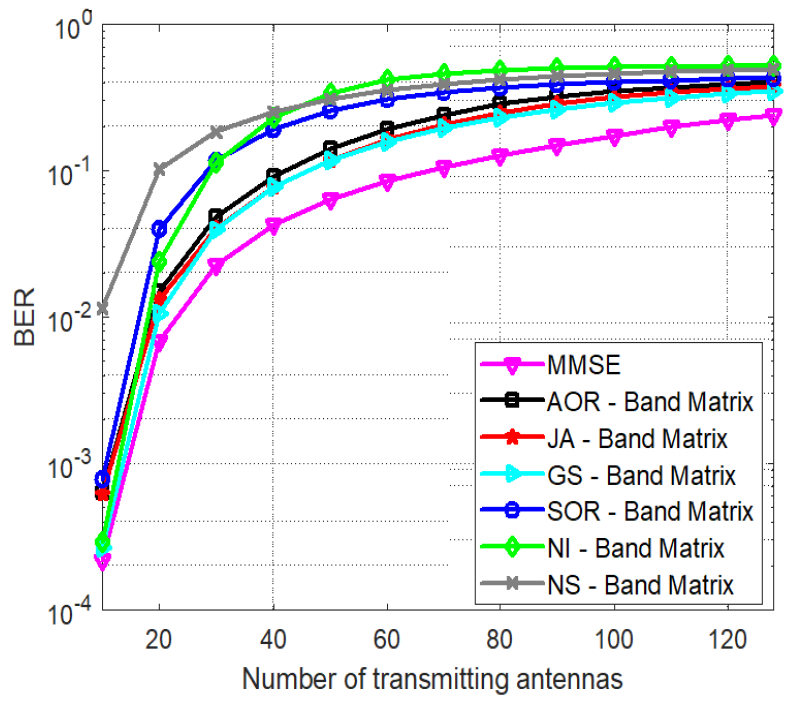

We next explore impact of increasing users’ number on BER performance of proposed methods, for λ = 1 (Fig. 5), while fixing the SNR at 13 dB and BS antennas’ number at N = 128. As expected, the performance of all methods gradually deteriorates as users’ number increases.Among the proposed methods, the GS offers the slowest degradation as the number of users increases. The performances of the JA and AOR are only slightly worse than the GS, while the remaining three methods tend to deteriorate faster with the number of users.

Fig. 5.

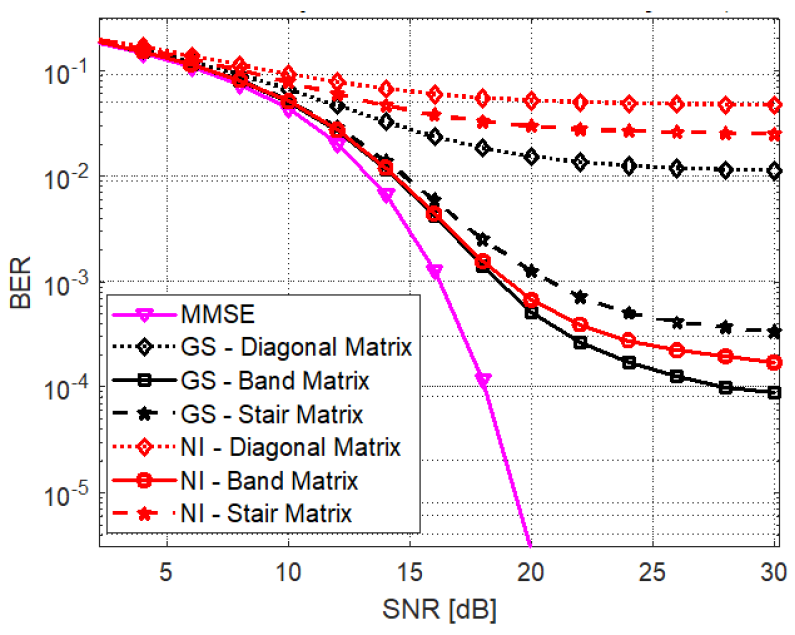

In Fig. 6, we consider the best methods of the two approaches (GS for the iterative linear equation approach and NI for the approximate matrix inversion approach) and compare the BER performances of the band matrix, diagonal matrix and stair matrix formulations. We consider a 24×128 mMIMO system, and use n = 1 iterations for all methods and λ = 5 for the band matrix. For the GS method, while both the band matrix and stair matrix formulations are significantly better than the diagonal formulation, the band matrix formulation offers [TeX:] $$\approx 2 \mathrm{~dB}$$ gain compared to the stair matrix at BER of [TeX:] $$10^{-3}$$, and [TeX:] $$\approx 7.5 \mathrm{~dB}$$ at [TeX:] $$\mathrm{BER}=3 \times 10^{-4}.}$$ For the NI method, on the other hand, the band matrix formulation offers a huge gain compared to both other formulations. For low BER values (e.g., [TeX:] $$3 \times 10^{-1}.$$), the band matrix NI offers a gain of [TeX:] $$\approx 4 \mathrm{~dB}$$ compared to the stair matrix and 10 dB compared to the diagonal matrix. However, the band matrix formulation achieves BER as low as [TeX:] $$2 \times 10^{-4}.$$ at high SNR, while the other two formulations do not go below [TeX:] $$2 \times 10^{-2}.$$ It is also clear that band matrix based detectors can support more users than detectors based on diagonal matrix and stair matrix.

Fig. 6.

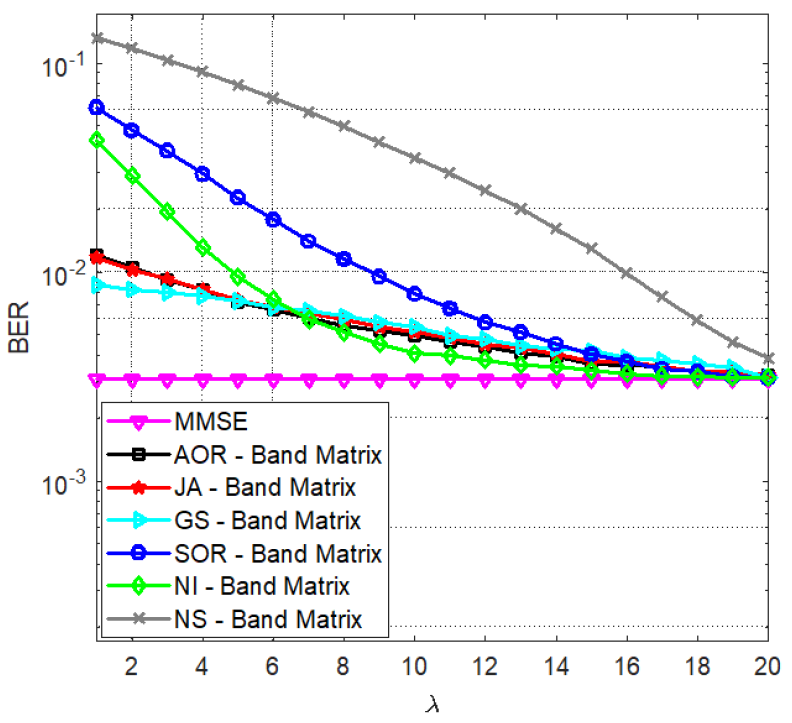

In Fig. 7, we investigate the performance of the proposed methods versus the bandwidth λ of the band matrix. In particular, for a 24×128 mMIMO system, we plot the BER of all the methods versus λ, for n = 1 and SNR of 15 dB. As expected, all the BER performances improve as λ increases, eventually, approaching MMSE performance. For small values of λ, the GS offers the best performance, followed by the JA and the AOR. However, as λ increases, eventually the NI outperforms other methods for the same value of λ, and is the first to approach MMSE performance. While the NS and SOR still approach the MMSE for high value of λ, they require high values of λ (16 for the SOR and 20 for the NS) to perform close to MMSE. It should be noted, however, that the computational complexity of all methods increases with λ as discussed in Section IV. Hence, the GS may be more desirable than the NI for small values of λ.

Fig. 7.

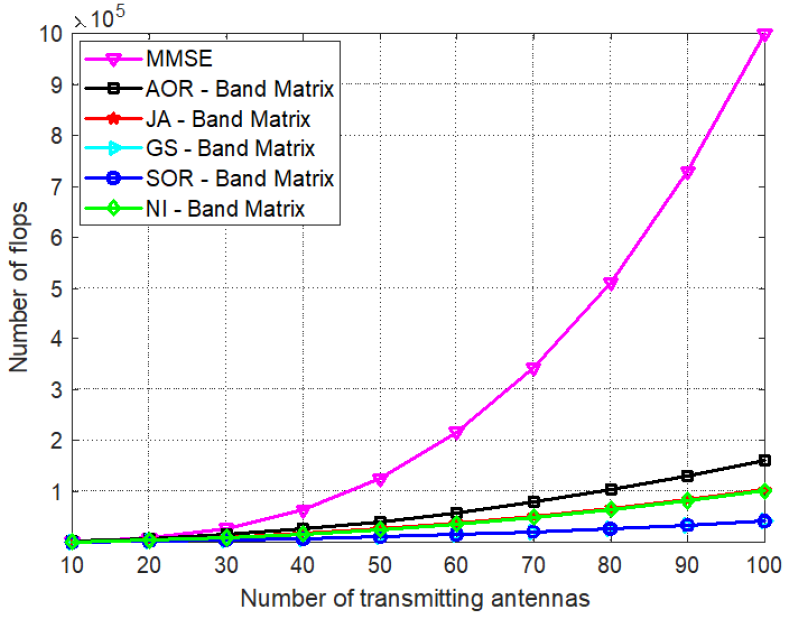

Figure 8 illustrates a performance comparison between the proposed detectors and the detector in [28] under imperfect CSI. The imperfect channel modeled by [TeX:] $$\hat{\mathbf{H}}=\xi \mathbf{H}+\sqrt{\mathbf{1}-\xi^2} \mathbf{N},$$ where ξ = 0.8. It is evident that the proposed detectors, with the exception of the JA based detector, outperform the detector in [28]. Finally, in Fig. 9, we compare the computational complexities of all the proposed band matrix methods to that of the MMSE, in terms of flops’ number as usres’ number increases. We set λ = 1 and n = 2, while the number of BS antennas is set to 128. It is observed that all methods have a significantly lower complexity that the MMSE. The SOR and GS have the lowest complexity, whereas those of the NI and JA almost overlap. The AOR has the highest complexity among the proposed methods. In general, this simulation confirms that the band matrix formulation offers a very significant improvement in computational complexity compared to the MMSE.

Fig. 8.

VI. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we addressed the data detection problem in mMIMO systems and developed six mMIMO detectors: the AOR-band matrix, SOR-band matrix, GS-band matrix, JAband matrix, NI-band matrix, and NS-band matrix. The simulation results demonstrated that the parameter λ significantly affects both the performance and computational complexity of all the proposed detectors. While increasing λ enhances performance, the improvement plateaus near MMSE performance beyond a certain λ value, making careful selection of λ essential to avoid unnecessary computations. We also introduced efficient initialization techniques based on the band matrix. The proposed detectors achieved notable BER performance (close to MMSE) with a significant reduction in complexity compared to conventional detectors using diagonal or stair matrices. Moreover, the detectors performed well even as users’ number approached the BS antennas’ number. A key advantage of the proposed GS-band matrix and NI-band matrix detectors is their ability to achieve MMSE performance without requiring a large iterations’ number or a high band parameter when receiving antennas’ number greatly exceeds transmitting antennas’ number. This highlights the superiority of band matrix-based detectors in supporting more users compared to diagonal and stair matrix-based approaches. In the future, we plan to extend these detectors to joint channel estimation and data detection in mMIMO systems. Furthermore, many implementation steps of the proposed detectors are inherently parallelizable, which can significantly reduce execution time with appropriate computational resources.

Biography

Mahmoud A. Albreem

Mahmoud A. Albreem (Senior Member, IEEE) received the B.E. degree in Electrical Engineering from the Islamic University of Gaza, Palestine, in 2008. He then earned both his M.Sc. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Malaysia, in 2010 and 2013, respectively.From2014to2016,Dr.Albreemserved as a Senior Lecturer at Universiti Malaysia Perlis. Between 2016 and 2021, he chaired the Department of Electronics and Communications Engineering at ASharqiyah University, Oman. He is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Sharjah, UAE. Dr. Albreem has authored over 90 journal and conference papers. His academic excellence has been recognized with several prestigious scholarships and awards, including the Nokia Foundation Centennial Grant (2018), the USM Fellowship (2011-2013), and the Best MasterâẠỎs Thesis Award from the School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering at USM (2010). He has also contributed to the field by serving on the Editorial Board of several journals. His research interests are primarily focused on MIMO detection and precoding techniques, machine learning applications for wireless communication systems, and green communications.

Biography

Saeed Abdallah

Saeed Abdallah (Member, IEEE) received the B.E. degree in Computer and Communications Engineering from the American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, in 2005, and the M.Sc. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, in 2008 and 2013, respectively. He held the position of a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, QueenâẠỎs University, Kingston, ON, Canada, from 2013 to 2014. Since 2014, he has been with the Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, where he currently holds the rank of an Associate Professor. His research interests include signal processing for wireless communications, with special emphasis on beyond fifth generation (B5G) wireless communications, ambient backscatter communication systems, molecular communications, massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) systems, relay networks, channel estimation, and synchronization.

Biography

Mohamed Saad

Mohamed Saad (Senior Member, IEEE) received the Ph.D. degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering from McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada,in2004.HeiscurrentlyProfessorandChair oftheDepartmentofComputerEngineering,University of Sharjah, UAE. His research interests include networking,communications,andoptimization,with current activity focused on the optimal design of wireless and wired communication networks, and optimal network resource management. He has also heldresearchpositionswiththeDepartmentofElectrical and Computer Engineering, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada, and the Advanced Optimization Laboratory at the Department of Computing and Software, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada. Prof. Saad is an associate editor for Frontiers in Communications and Networks. He was the Recipient of the Best Paper Award in the IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications, Riccione, Italy, June 2010. He was the Recipient of the University of Sharjah âẠỦAnnual Incentive Award for Distinguished Faculty MembersâẠŨ, for excellence in research, April 2010 (universitywide). He also received two Best Teaching Awards by the IEEE Women in Engineering Society, University of Sharjah (in 2007 and 2009). He was also the Recipient of a 2005-2006 Natural Sciences and Engineering Research CouncilofCanada(NSERC)post-doctoralfellowship.HeisaSeniorMember of the IEEE.

Biography

Mahmoud Aldababsa

Mahmoud Aldababsa (Member, IEEE) received a B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering from AnNajah National University, Palestine, in 2010, an M.Sc. degree in Electronics and Communication Engineering from Al-Quds University, Palestine, in 2013, and a Ph.D. degree in Electronics Engineering from Gebze Technical University, Turkey. He was a Research and Teach Assistant at Al-Quds University from 2010 to 2013. He was a Post-Doc Researcher at the Communications Research and Innovation Laboratory (CoreLab) at Koc University, Turkey. He was an Assistant Professor of Electrical and Electronics Engineering at Istanbul Gelisim University, Turkey, and is currently at Nisantasi University. His current research interests include non-orthogonal multiple access and reconfigurable intelligent surfaces in 5G and 6G wireless systems.

Biography

Mohamed Saad

KHAWLA A. ALNAJJAR (Member, IEEE) received the B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering and Communication track from United Arab Emirates University (UAEU), Al Ain, in 2008, the M.S. and P.E.E. degrees in Electrical Engineering from Columbia University, New York, in 2010 and 2012, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree in electrical and electronics engineering from the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, in 2015. She is currently an Assistant Professor with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Her research interests include wireless communication systems, mathematical statistics, network information theory, and power grids. She has received more than 30 competitive awards for her successful studies and research during these ten years.

References

- 1 M. A. Albreem, A. H. Al Habbash, A. M. Abu-Hudrouss, and M.-T. EL Astal, "A low-complexity detection framework for signed quadrature spatial modulation based on approximated MMSE sparse detectors," IEEE Syst. J., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-11, 2025.custom:[[[-]]]

- 2 E. G. Larsson, O. Edfors, F. Tufvesson, and T. L. Marzetta, "Massive MIMO for next generation wireless systems," IEEE Commun. Mag., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 186-195, 2014.custom:[[[-]]]

- 3 F. Rusek et al., "Scaling up MIMO: Opportunities and challenges with verylargearrays," IEEE Signal Process. Mag.,vol.30,no.1,pp.40-60, 2012.custom:[[[-]]]

- 4 M. A. Albreem, S. Abdallah, K. A. Alnajjar, and M. Aldababsa, "Efficient detectors for uplink massive MIMO systems," J. Commun. Netw., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 35-48, 2024.custom:[[[-]]]

- 5 M. A. Albreem, M. Juntti, and S. Shahabuddin, "Massive MIMO detection techniques: A survey," Commun. Surveys Tuts., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 3109-3132, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 6 M. Albreem, M. Juntti, and S. Shahabuddin, "Efficient initialisation of iterative linear massive MIMO detectors using a stair matrix," Electron. Lett., vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 50-52, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 7 M.A.Albreem,A.H.Alhabbash,S.Shahabuddin,andM.Juntti,"Deep learning for massive MIMO uplink detectors," Commun. Surveys Tuts., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 741-766, 2022.custom:[[[-]]]

- 8 M. A. Albreem et al., "Low complexity linear detectors for massive MIMO: A comparative study," IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 45740-45753, 2021.custom:[[[-]]]

- 9 H.Prabhu,J.Rodrigues,O.Edfors,andF.Rusek,"Approximativematrix inverse computations for very-large MIMO and applications to linear pre-coding systems," in Proc. IEEE WCNC, 2013.custom:[[[-]]]

- 10 X. Zhang, H. Zeng, B. Ji, and G. Zhang, "Low-complexity implicit detection for massive MIMO using Neumann series," IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 71, no. 8, pp. 9044-9049, 2022.custom:[[[-]]]

- 11 C. Tang, C. Liu, L. Yuan, and Z. Xing, "High precision low complexity matrix inversion based on Newton iteration for data detection in the massive MIMO," IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 490-493, 2016.custom:[[[-]]]

- 12 F. Jin, Q. Liu, H. Liu, and P. Wu, "A low complexity signal detection scheme based on improved Newton iteration for massive MIMO systems," IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 748-751, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 13 L. Dai et al., "Low-complexity soft-output signal detection based on Gauss-Seidel method for uplink multiuser large-scale MIMO systems," IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 4839-4845, 2014.custom:[[[-]]]

- 14 X. Gao, L. Dai, Y. Hu, Z. Wang, and Z. Wang, "Matrix inversionless signal detection using SOR method for uplink large-scale MIMO systems," in Proc. IEEE GLOBECOM, 2014.custom:[[[-]]]

- 15 Y.Hu,Z.Wang,X.Gaol,andJ.Ning,"Low-complexitysignaldetection using CG method for uplink large-scale MIMO systems," in Proc. IEEE ICCS, 2014.custom:[[[-]]]

- 16 B. Y. Kong and I.-C. Park, "Low-complexity symbol detection for massiveMIMOuplinkbasedonJacobimethod,"in Proc. PIMRC,2016.custom:[[[-]]]

- 17 S. Berra, M. A. Albreem, and M. S. Abed, "A low complexity linear precoding method for massive MIMO," in Proc. IEEE UCET, 2020.custom:[[[-]]]

- 18 J. Minango and C. De Almeida, "Optimum and quasi-optimum relaxation parameters for low-complexity massive MIMO detector based on Richardson method," Electron. Lett., vol. 53, no. 16, pp. 1114-1115, 2017.custom:[[[-]]]

- 19 M. Nauman Irshad, M. Muzamil Aslam, and R. Silapunt, "Low complexity optimized AOR method for massive MIMO signal detection," IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 51054-51068, 2025.custom:[[[-]]]

- 20 A. K. Imran, X. Zhang, H. S. Abdul, A. K. Ihsan, and A. D. Zaheer, "Low-complexity signal detection for massive MIMO systems via trace iterative method," J. Syst. Eng. Electron., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 549-557, 2024.custom:[[[-]]]

- 21 S. Shahabuddin, M. A. Albreem, M. S. Shahabuddin, Z. Khan, and M. Juntti, "FPGA implementation of stair matrix based massive MIMO detection," in Proc. IEEE LASCAS, 2021.custom:[[[-]]]

- 22 F. Jiang, C. Li, Z. Gong, and R. Su, "Stair matrix and its applications to massive MIMO uplink data detection," IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 2437-2455, 2018.custom:[[[-]]]

- 23 M. A. Albreem and K. Vasudevan, "Efficient hybrid linear massive MIMO detector using Gauss-Seidel and successive over-relaxation," International J. Wireless Inf. Netw., vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 551-557, 2020.custom:[[[-]]]

- 24 S. Chakraborty, N. B. Sinha, and M. Mitra, "Likelihood ascent searchaided low complexity improved performance massive MIMO detection in perfect and imperfect channel state information," International J. Commun. Syst., vol. 35, no. 8, 2022.custom:[[[-]]]

- 25 L. N. Ribeiro, A. L. de Almeida, and J. C. M. Mota, "Separable linearly constrained minimum variance beamformers," Signal Process., vol. 158, pp. 15-25, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 26 T. L. Marzetta, "Noncooperative cellular wireless with unlimited numbers of base station antennas," IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 3590-3600, 2010.custom:[[[-]]]

- 27 C. Tang, C. Liu, L. Yuan, and Z. Xing, "High precision low complexity matrix inversion based on Newton iteration for data detection in the massive MIMO," IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 490-493, 2016.custom:[[[-]]]

- 28 J. Minango and C. de Almeida, "Low complexity zero forcing detector based on Newton-Schultz iterative algorithm for massive MIMO systems," IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 11759-11766, 2018.custom:[[[-]]]

- 29 F. Jin, Q. Liu, H. Liu, and P. Wu, "A low complexity signal detection scheme based on improved Newton iteration for massive MIMO systems," IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 748-751, 2019.custom:[[[-]]]

- 30 Z. Wu, Y. Xue, X. You, and C. Zhang, "Hardware efficient detection for massive MIMO uplink with parallel Gauss-Seidel method," in Proc. DSP, 2017.custom:[[[-]]]

- 31 G. Avdelas and A. Hadjidimos, "Optimum accelerated overrelaxation method in a special case," Mathematics Comput., vol. 36, no. 153, pp. 183-187, 1981.custom:[[[-]]]

- 32 L.-B. Cui, C.-X. Li, and S.-L. Wu, "The relaxation convergence of multisplitting AOR method forlinear complementarity problem," Linear Multilinear Algebra, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 40-47, 2021.custom:[[[-]]]

- 33 B. Y. Kong and I.-C. Park, "Low-complexity symbol detection for massiveMIMOuplinkbasedonJacobimethod,"in Proc. PIMRC,2016.custom:[[[-]]]

- 34 H. Lu, "Stair matrices and their generalizations with applications to iterative methods I: A generalization of the successive overrelaxation method," SIAM J. Numerical Anal., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 1-17, 1999.custom:[[[-]]]

- 35 D. K. Salkuyeh, "Generalized AOR method for solving system of linear equations," Australian J. Basic Applied Sci., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 351-358, 2011.custom:[[[-]]]

- 36 R.-S. Ran and T.-Z. Huang, "An inversion algorithm for a banded matrix," Comput. Mathematics Appl., vol. 58, no. 9, pp. 1699-1710, 2009.custom:[[[-]]]

- 37 G. H. Golub and C. F. Van Loan, "Matrix computation", JHU press, 2013.custom:[[[-]]]